Entitlement reform and retirement benefits

In this article we begin with a brief update on the current timing of coming ‘budget battles’ and then discuss the extent to which possible changes in Social Security rules, intended to reduce entitlement expenditures, may affect retirement plans.

The current state of the budget battles

So far this year, Congress has passed a fix to the ‘fiscal cliff’ (on January 2), allowed the ‘sequester’ budget cuts to take effect (on March 1) and passed a continuing resolution to fund the government through September (on March 21). It looks like the next big budget battle will be over an increase in the debt ceiling. Current thinking is that the federal government is on track to hit the debt limit in May 2013 but that Treasury will be able to use ‘extraordinary measures’ to push the ‘real’ debt ceiling deadline back to July or August.

It also looks like House Republicans are getting ready for another fight on the debt ceiling (like the one in 2011). House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) recently said that the plan was to ask for one dollar in spending cuts for every one dollar in debt ceiling increase. House Republicans have also said that spending cuts will probably have to come from savings in entitlement spending – that they are, in effect, running out of possible discretionary spending cuts.

Two changes to Social Security have been discussed that would have an effect on private retirement plans: an increase in the Social Security retirement age and means testing benefits.

Increasing the Social Security retirement age

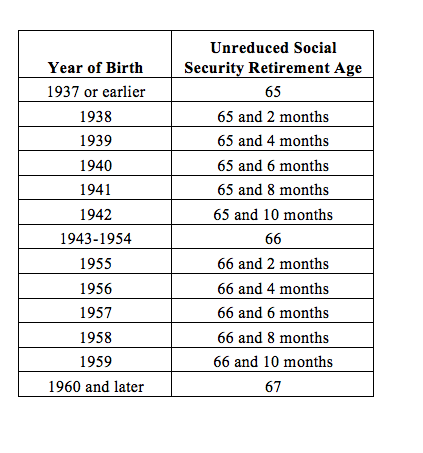

Currently, the Social Security retirement age (SSRA) is as follows:

Most defined benefit plans target a retirement age of 65, and indeed ERISA rules generally preclude normal retirement ages greater than 65.

Retirement income modeling in DC plans is typically more flexible — allowing the participant to choose a target retirement age. But it’s probably fair to say that participants’ current bias is towards an age 65 retirement age target.

The challenge for plans

A change in the SSRA presents an explicit challenge for DB plans, because those plans generally premise their benefit on a normal retirement age. It also presents an implicit challenge for account-based designs like cash balance or DC plans, at least to the extent the plan design focuses on enabling a participant to accumulate an adequate benefit at some assumed ‘retirement age.’

When the SSRA was increased in 1983, sponsors generally did not re-conceptualize DB plan design to reflect that change. An increase in the SSRA to 70 may have more dramatic consequences. Critically, for companies that perform complex nondiscrimination testing, changes to Social Security may prompt corresponding changes to ‘permitted disparity’ rules that reflect the value of Social Security. Thus, a change in the SSRA may compel some companies to redesign their plans in order to stay in compliance.

Alternative responses

If the SSRA is increased to age 70, sponsors are faced with three obvious alternatives.

Alternative 1 – do nothing. Certainly the simplest alternative, in that it generally will require the fewest tough decisions. DB plans that are integrated with Social Security may get more expensive or may require design changes; cash balance and DC retirement income models that include the value of Social Security will start producing new (and lower) results. But in the abstract (and disregarding the integration issue), the amount coming from Social Security will go down and the amount the sponsor provides will remain the same. The result, retirement pay for participants at the plan’s NRA will be smaller.

Alternative 2 – make up the difference. Theoretically this would require re-designing plan benefits to produce the same gross benefit – plan benefit + Social Security benefit – that was available before the change in SSRA. Obviously, in DB plans, the cost of this approach will vary depending on plan design. In DC plans the issue will be how much more savings/contributions are necessary to hit the same age 65 retirement income target.

Alternative 3 – increase the target retirement age to, say, age 70. For DB plans, there are legal obstacles to adopting a ‘normal’ retirement age greater than 65, and anti-cutback rules will prevent any reduction to accrued benefits, but ‘reframing’ the retirement decision around a later age may allow for a reduced rate of benefit accrual. Generally this approach will reduce plan costs; again, the amount of savings will depend on current plan design. For cash balance and DC plans the issue will be one of expectations. Shifting the retirement age target from 65 to 70 will, in effect, lower expectations all around.

Traditional DB plans

For traditional DB plans – plans that provide benefits based on an annuity formula – there are some special issues worth identifying.

If the DB plan is a flat dollar plan (e.g., a benefit formula of an annuity beginning at age 65 of $200 per year x years of service), doing nothing will result in a significant reduction in the gross benefit (plan benefit + Social Security benefit), even though the plan benefit is unchanged.

In the typical integrated final pay plan, doing nothing may result in some increase in the plan benefit, because the value of the integrated Social Security benefit is going down. But plans generally can only integrate a portion of the Social Security benefit, and many integrate less than the fully allowable amount. So while the plan benefit will go up, the gross benefit (plan benefit + Social Security benefit) will go down.

Broader considerations

Changing demographics, of which changing retirement ages is an aspect, present challenges for sponsor human resources departments that go beyond plan design and finance. Many companies are concerned about the loss of skill and experience as the (large) baby boom cohort retires and is replaced by the (smaller) following generation. That sounds abstract; in real life it is a question for some companies of not having enough workers with the needed skills and experience because they are all retiring.

In that context, it may not be in the sponsor’s interest to encourage older workers to retire. Thus, moving to an age 70 retirement target may be a good idea. On the other hand, it is not in the sponsor’s interest to punish those older workers. Thus, HR may want to explore different incentives – higher pay? a bigger post-age 70 benefit? – for these workers.

Means testing

There has also been talk amongst both Republicans and (to a lesser extent) Democrats of means testing Social Security. It was said to be part of the ‘Gang of Six’ Senate negotiations over a ‘grand bargain’ in 2011, and, according to politico.com, President Obama is ‘open to it.’ At this point there are few concrete means testing proposals, but there have been discussions of raising the retirement age or reducing benefits for certain income groups.

An increase in the Social Security retirement age only for “high earners” presents an interesting retirement plan design challenge. Consider: in an integrated “offset” plan, if the employer does nothing, then the benefit for higher-paid (means-tested) participants would go up relative to the benefit for lower-paid (non-means-tested) participants. That might present an issue under Tax Code nondiscrimination rules – or not, depending on how those rules are applied. It also presents an interesting question of benefits policy – should policymakers give back in the Tax Code what they are taking away in Social Security? And for sponsors, should the employer make up for what policymakers have decided ‘high paid employees’ don’t need?

Even more problematic for sponsors would be the proposal, argued for by (among others) Heritage Foundation Fellow David John in a recent AARP Public Policy Institute Perspective, to reduce Social Security benefits based on retirement income. In that Perspective John outline a plan to reduce Social Security benefits by 1.8% for every $1,000 of “non-Social Security retirement income” over $55,000. Such a rule would, in effect, function as an additional (and significant) tax on retirement benefits (whether from a defined benefit or a defined contribution plan) and would, at the margin, discourage retirement saving and retirement benefits generally. To get an idea of how significant that tax would be, consider a participant receiving $75,000 per year in non-Social Security retirement income. This participant would have to pay, in effect, a new tax on her Social Security benefit of 36 percent ($75,000 – $55,000 = $20,000/$1,000 = 20 x 1.8% = 36%).

There are a lot of open questions about means testing. Most importantly, how do you define ‘means?’ The David John proposal looks at retirement income. But others have suggested looking at ‘wealth,’ perhaps measured by lifetime income.

Conclusion

All of this is still in the very early stages. But as the debate over entitlements policy develops, sponsors will want to think through the implications for company retirement policy and plan design.