PBGC’s Single Employer Deficit and PBGC Premiums

PBGC's Single Employer Deficit and PBGC Premiums

In prior articles we have discussed recent increases in Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation premiums, and possible future increases that may be ‘on the table’ in budget negotiations. PBGC premiums count, for government budget purposes, as revenues; they are viewed by some as a less onerous ‘revenue enhancement’ than, e.g., a broad tax increase; thus they make an appealing ‘budget gap closer.’ But the fundamental reason given for increasing PBGC premiums is PBGC’s deficit.

In this article we review just what goes into PBGC’s deficit numbers and, briefly, the debate over how realistic they are. Our analysis is based on the PBGC’s fiscal year 2012 annual report, which was prepared as of September 30, 2012, and is limited to the PBGC’s ‘single-employer’ insurer program (multi-employer plans are insured separately by the PBGC.)

We begin with some background on the PBGC and its role in debates over the larger issue of DB plan funding.

The significance of the PBGC

The PBGC does not have the Department of Labor’s broad authority to set rules for fiduciary conduct or IRS’s authority to set rules for nondiscrimination testing and funding. But, for the defined benefit plan system, the existence of the PBGC ‘changes everything.’ Critically, all rules about funding must ultimately be measured against their consequences for the PBGC.

Indeed, perhaps the most important factor leading to the adoption of ERISA in 1974 was the bankruptcy of DB plan sponsors (the Studebaker bankruptcy is often singled out) that left retirees — dependent on the bankrupt companies’ pension plan benefits — with cents on the dollar. To prevent a recurrence of this ‘great personal tragedy’ (in the words of Senator Bentsen (D-TX)), the PBGC was established to insure pension benefits. If a plan terminated without enough money to pay benefits, then the PBGC would step in and (up to certain limits) pay those benefits.

This policy of insuring DB benefits raised three related policy challenges.

1. Funding adequacy.

While Congress may have had other policy goals in mind when, as part of ERISA, it established minimum funding standards for ERISA DB plans, it has become clear that if you, on the one hand, insure the unfunded benefits of insolvent DB plans through a federal agency, then you generally will want, on the other, to have a rigorous program of minimum contributions (ERISA’s minimum funding standards) to minimize insolvency risk.

In this regard, over time, it became clear that ERISA’s initial minimum funding standards, which, e.g., generally allowed funding of past service liability over 30 years, were too loose. And we have seen, over the last four decades (ERISA was generally effective in 1976), periodic efforts to tighten minimum funding standards, culminating in the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (which requires any shortfall to be funded over seven years).

2. Premium adequacy.

The initial single-employer plan premium was $1 per participant. Early on, this premium rate was recognized as inadequate, and it has been increased repeatedly over the years. Now, there are two separate components to the annual premium: the ‘per-participant’ premium payable by all plans ($42 in 2013, increasing to $49 in 2014 and indexed to national average wages thereafter), and a variable premium based on a plan’s ‘unfunded vested benefits’, if any (0.9% of such amount, increasing to 1.3% in 2014 and 1.8% in 2015, with this percentage(!) indexed to national average wages thereafter.) The current structure reflects MAP-21 premium increases that have been estimated to bring in about $9 billion in additional revenue over 10 years.

3. Liability ‘dumping.’

As originally structured, under Title IV of ERISA (which establishes the PBGC and the benefit insurance system), a company could, in some cases, reorganize, lay unfunded DB liabilities off on the PBGC, and continue in operation. Critics described this as ‘dumping’ liabilities on the PBGC. Congress ultimately tightened these rules, requiring, generally, that a company cannot emerge from bankruptcy unless it is able to transfer liabilities to the PBGC.

None of these issues – minimum funding/insolvency standards, PBGC premium levels and PBGC’s status in bankruptcy – are considered ‘finally’ settled. Both PBGC and sponsors continue to battle over them.

We rehearse this brief history of the PBGC and PBGC-related policy to emphasize the importance of the PBGC in debates about DB funding — debates that have dominated DB-related policy discussions for most of the century. Indeed, last year, when Congress included funding relief in MAP-21 legislation, it also included a significant increase in PBGC premiums. The premium increase was ostensibly related to the issue of PBGC’s deficit. But it is inescapable that the issues of the funding and solvency of DB plans, on the one hand, and the funding and solvency of PBGC, on the other, are directly linked.

PBGC and federal budget

Finally, let’s consider how the issues of PBGC’s deficit and PBGC premiums relate to the broader federal budget. PBGC’s deficit – and the risks it presents generally – is not ‘on the books.’ The PBGC ‘deficit’ does not add to the federal ‘deficit,’ at least as it is calculated by Congress and the Administration. But it is generally believed that if, ultimately, PBGC does not have enough assets to pay insured benefits, then those benefits will have to be paid out of general revenues. The PBGC is much more like the FDIC than Fannie Mae, but some policymakers are concerned that, if funding standards are relaxed and/or premiums are not adequate, the PBGC may have to be bailed out ‘like Fannie Mae.’ Moreover, PBGC premiums count as revenues for purposes of the budget. This result is somewhat counterintuitive, given that the PBGC deficit is not ‘on the budget.’

These two ‘macro’ issues — the worst-case fear of a PBGC bailout and the status of PBGC premiums as revenues — set up an interesting (and somewhat bizarre) dynamic. Relaxing contribution standards increases revenues (for budget purposes): companies contribute less and therefore take smaller deductions. Increasing PBGC premiums (arguably justified by the increased risk that relaxed funding standards presents) also increases revenues. And so we saw Congress, in order to find a ‘pay for’ for highway expenditures, both relax contribution standards and increase PBGC premiums. All of which brings us to the issue of PBGC’s ‘deficit.’

How is PBGC’s ‘deficit’ defined?

Let’s begin with how PBGC defines its deficit. Quoting from “Understanding the Financial Condition of the Pension Insurance Program” (a set of FAQs released by PBGC):

The deficit includes losses incurred from plans that have already terminated and estimated losses incurred from “probable” terminations. A plan is classified as a probable termination if PBGC determines that it is likely the plan will terminate. Generally, a plan is classified as a probable termination if the employer is in liquidation and there are no related companies that could fund the plan; the employer has filed for a distress termination; or PBGC is seeking involuntary plan termination.

So — PBGC’s deficit only includes liabilities that either are, or are very likely to be, on the books. (‘Probable’ terminations generally make up less than 1% of total liabilities.) ‘Possible’ future terminations are not part of PBGC’s deficit. Only liabilities that have, in effect, already been assumed by the PBGC are counted.

How much is PBGC’s deficit?

As of September 30, 2012, PBGC reported its deficit with respect to the single-employer program as $29.1 billion, reflecting benefit-related liabilities of $112.1 billion and assets of $83.0 billion. The deficit is up from around $23.3 billion in 2011, and from just $10.7 billion in 2008. So, the size of PBGC’s deficit for single-employer plans has almost tripled over four years. How did that happen?

Why is PBGC’s deficit so big?

PBGC budget/deficit calculations are a bit complicated, but there are three key pieces to the story of the PBGC deficit since 2008: (1) ‘losses’ due to the passage of time; (2) ‘losses’ due to declines in interest rates; and (3) ‘gains’ due to returns on trust assets.

(Fully funded pension plans can more or less ‘immunize’ themselves against financial markets by investing in a portfolio of bonds with maturities that match the benefit payment cash flows. In this case, ‘gains’ on trust assets move in tandem with the ‘losses’ due to the passage of time and changes in interest rates. Obviously, over the last four years, that did not happen for PBGC.)

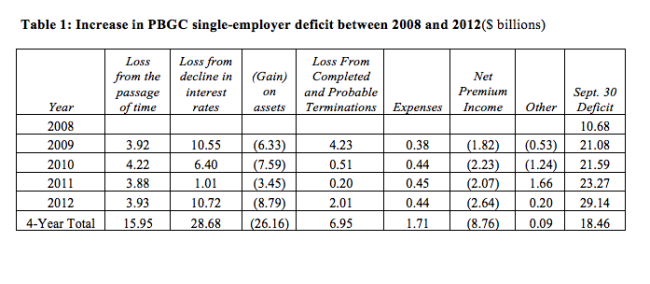

The following table summarizes the items producing the increase in the PBGC’s single-employer program between September 30, 2008 and September 30, 2012:

The chart shows that the increase in the PBGC deficit over the past four years ($18.46 billion) is almost completely explained by the ‘big three’ items (loss from the passage of time, loss from declines in interest rates and gain on trust assets, totaling $18.47 billion).

Also troubling, however, is a recurrent pattern of ‘losses from completed and probable terminations’ during this period which, combined with PBGC expenses, has essentially consumed all of the $8.76 billion in premium income over the past four years. In other words, even if the PBGC had not suffered ‘experience losses’ based on asset and interest rate movements, it would not have made any headway on the $10.68 billion deficit at September 30, 2008.

Criticism of PBGC’s valuation policies

In the past, some have criticized PBGC’s liability valuation interest rate policy as too conservative. PBGC relies on a survey of annuity purchase rates which are generally lower than the high quality corporate bond rates used to value liabilities for funding purposes: the rate PBGC uses to value liabilities as of September 30, 2012 is 3.28%, while the September 2012 ‘spot’ yield curve required under PPA produces rates around 4%.

More recently, the criticism has moved to the more general one that current interest rates are “artificially low,” that they reflect Federal Reserve monetary policy and not any underlying economic reality. This is the same argument made with respect to funding rates that resulted in funding relief under MAP-21. (We discuss the impact of declines in interest rates on DB liabilities and Fed policy in our article How low can you go? Interest rates and DB plans.)

Thus, we return to the point we made at the beginning: the issues of the funding and solvency of DB plans, on the one hand, and the funding and solvency of PBGC, on the other, are directly linked. What has happened to the PBGC looks a lot like what happened to many DB plan sponsors over the same four-year period 2009-2012. Unless a DB plan sponsor pursued an aggressive liability driven investment program, it saw its funding position weaken more or less in the same way PBGC’s deficit has increased. And the arguments made for MAP-21 funding relief — which established an interest rate floor based on a 25-year average of interest rates — logically also apply to PBGC’s valuation methodology — at least to the extent that PBGC’s deficit is made the premise for possible increases in PBGC premiums.

“New” liabilities and premiums

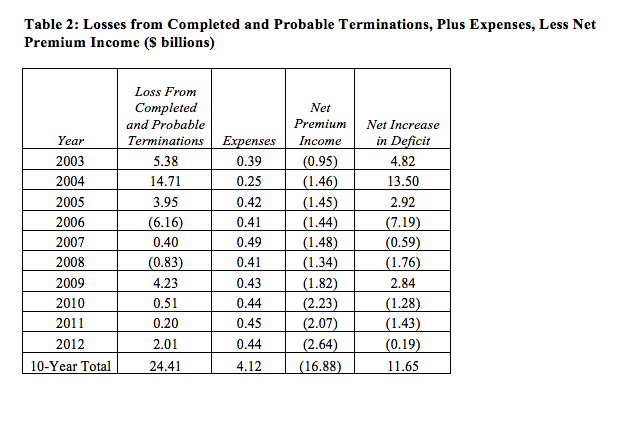

Using the idealized model we’ve been considering, current assets would equal current liabilities, and interest rate-related losses on liabilities would be offset by gains on assets. That gains on assets did not offset interest rate-related losses over the last four years explains (as we show above) the $18.5 billion increase in PBGC’s deficit for the period 2009-2012. Using that same model, any increase in liabilities because of, e.g., new plan terminations ideally would be offset by premium income. The table below shows premiums and newly added liabilities for the period 2003-2012.

Over the past 10 years, the impact of new and completed terminations plus expenses have significantly outpaced premium income collected (by $11.65 billion), although, in fairness, all of this shortfall (and then some) can be attributed to 2004, with the bulk of that due to a small number of high profile bankruptcies among airlines. So, if the story of PBGC’s deficit for the last four years has been about a mismatch between assets and liabilities, most of the existing deficit at September 30, 2008 ($0.68 billion) can be understood as the ‘legacy’ of events in the first part of the century. Still, as we saw above, even if we discount the airline bankruptcies, most of the premiums collected over the past several years have gone toward the cost of new terminations and PBGC expenses, rater than addressing the existing PBGC deficit.

One interpretation (given the complexity of these matters, there are certainly others) of what we are saying is that losses during the period 2002-2008 can be attributable to, in effect, underwriting issues – premiums that did not cover losses related to new terminations – and that losses from 2009-2012 can be attributable to, in effect, investment policy issues — interest rate-related losses on liabilities that were already on the books and were not compensated for by gains on PBGC’s asset portfolio.

We note also that the relationship between premiums and termination losses is more discontinuous (“lumpy”) than the relationship between asset returns and interest rate losses. There are correlations between the returns on some assets and interest rate losses. But as we can see from the numbers, terminations come in big and often business cycle-related waves, while premiums come in steady increments.

PBGC premiums and the coming debate over the budget

As we have said before, many believe that an increase in PBGC premiums will be an element of 2013 budget negotiations. The $5.9 billion increase in the PBGC’s single-employer deficit during 2012 provides a basis for arguing for another round of premium increases. The ‘push back’ from the sponsor community will be – as described above – that these rates are unrealistically low and likely to be temporary (in fact, rates right now are about 30 basis points higher than they were last September) and that they therefore should not drive premium policy.

We will continue to follow this issue.