The ‘fiscal cliff’ and retirement plan participants

Policymakers are, post-election, almost entirely focused on the issue of the ‘fiscal cliff’- a combination of tax increases and spending cuts due to take effect automatically at the end of 2012. The two most significant elements of the fiscal cliff for retirement plan participants are a possible increase in federal income tax rates and a possible reduction in the limits on contributions to tax-qualified plans.

In the current lame ducks session, Congress will choose from among three options: do nothing and allow the tax rates to increase automatically on January 1, reach some sort of ‘grand bargain’ on comprehensive tax reform, or do something temporary and push the issue of the fiscal cliff into 2013.

There are multiple variations on each of these alternatives. For instance, President Obama is proposing changes that will avoid the fiscal cliff, but an essential element of his proposal is to increase the rate top-income earners pay from 35% to 39.6%. Republicans have proposed avoiding the fiscal cliff by, among other things, reducing marginal tax rates and eliminating tax expenditures (deductions and exclusions).

In this article we compare the effect on 401(k) plan participants of three alternatives: (1) an increase in marginal tax rates (which could take place either if Congress simply “lets the fiscal cliff happen” or if in “solving” the fiscal cliff Congress increases marginal tax rates); (2) a reduction in the limit on 401(k) plan contributions; and (3) a combination of a decrease in marginal tax rates and a reduction in limits (an approach that has been a part of some comprehensive tax reform proposals).

As with our recent article The value of retirement benefits and tax policy (reviewing what is at stake for participants in the “comprehensive tax reform” debate), we are going to focus exclusively on defined contribution/401(k) plans, because those plans are likely to be the focus of policymakers. And we will generally focus on high margin taxpayer/participants, because the impact of changes will generally be greatest for them. Our analysis is very similar to the one we used in the earlier article, except this time we are going to consider (among other things) the impact of an increase in marginal rates.

We begin with a summary and then proceed with a more detailed discussion of the results.

Summary

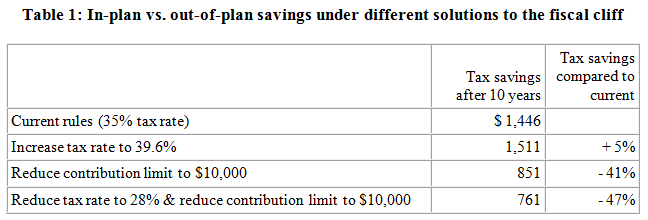

Table 1 summarizes the impact on the value of saving in a 401(k) plan to a high margin taxpayer/participant of three different solutions to the fiscal cliff: increasing the highest marginal tax rate to 39.6%; keeping the current rate (35%) but limiting annual 401(k) contributions to $10,000 (currently the limit is $17,000); or reducing the current rate to 28% and limiting annual 401(k) contribution to $10,000. “Tax savings” is the difference between how much money the taxpayer/participant has, after 10 years, if she saves $17,000 in a 401(k) plan or pays taxes on the $17,000 and saves the net amount outside a plan. (Our other assumptions are explained in detail below.)

Bottom line: an increase in marginal rates makes 401(k) savings more attractive. A reduction in limits or a reduction in marginal rates makes them less attractive.

In what follows we analyze these numbers in detail. We begin with a review of the tax effects under the current system.

The value to participants of the current system

We’re going to begin with a base case describing the value of current retirement savings tax incentives, with which we will then compare different alternatives. (This analysis is identical to the analysis in our prior article — we repeat it here simply to provide a baseline.)

Currently a taxpayer in the highest marginal federal income tax rate bracket, 35%, can make an excludible contribution to a 401(k) plan of $17,000 in 2012 (ignoring ‘catch up’ contributions). The contribution goes into a non-taxable trust. When the contribution and any trust earnings are paid out, the taxpayer pays taxes on the entire distribution.

How much is this favorable tax treatment worth? For our base case we’re going to assume that:

The taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is the same in the year of contribution and the year of payout, and the same rate is applied to ‘out-of-plan’ investment earnings.

Investments earn 3% per year.

The money remains in the trust for 10 years.

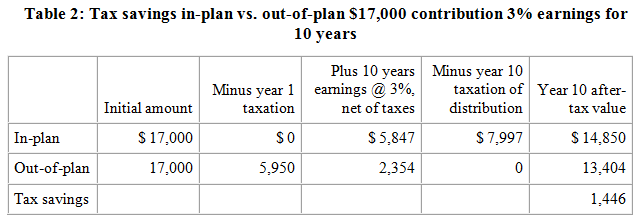

In this case, given a $17,000 contribution in year 1, in year 10 the taxpayer will get a payout of $22,847, and after she pays taxes on that distribution (at a 35% rate), she will have $14,850.

If she didn’t contribute to the plan, how much would she have? After paying taxes in year 1, the $17,000 is reduced to $11,050. If the taxpayer invests that amount in taxable investments paying an annual (before tax) return of 3%, then in year 10 she will have $13,404.

Thus the difference in value between in-plan savings and out-of-plan savings, in year 10, is $14,850 – $13,404 = $1,446. In year 10 the taxpayer will have $1,446 more if she saves in the plan than if she saves outside the plan.

There are a number of nuances that affect these results, including what earnings rate you pick, tax rates on alternative savings opportunities (certainly, in negotiations over the fiscal cliff, the issue of capital gains tax rates is on the table), and whether the taxpayer/participant in fact does have identical tax rates when the contribution is made and when it is distributed. We refer you to our earlier article for a discussion of those issues.

* * *

That’s the current “deal.” Now, let’s consider what happens if we “jump off the fiscal cliff” or adopt some new tax policy to avoid doing so. We begin by considering the effect of an increase in tax rates.

Effect of increased marginal rates

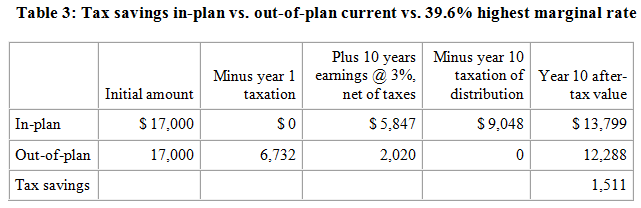

The marginal tax rate on the top-income earners would go up in at least two obvious scenarios: if the Congress simply “lets the fiscal cliff happen,” in which case the highest rate would go up to 39.6% automatically on January 1, 2013, or if, in solving/avoiding the fiscal cliff, Congress adopts President Obama’s proposal to increase the highest rate on top-income earners to 39.6%.

As we can see, if marginal tax rates go up, the value of saving in a plan vs. saving outside a plan goes up, in this case by $65, about 5%. Thus, if marginal tax rates go up, tax qualified retirement savings become more attractive.

We note that, generally, if the fiscal cliff happens, tax rates will go up on all taxpayers, so retirement savings will be more attractive to taxpayers in lower brackets as well. Under President Obama’s proposal, rates will only go up on top-income earners, and the tax incentives won’t change for those in lower brackets.

Reduction in contribution levels

The principal alternative to solving the fiscal cliff by increasing tax rates is to raise revenues by reducing/eliminating tax expenditures. Most believe that the 401(k) tax exclusion would be on the short list of tax expenditure reductions, probably through a reduction in the limits on contributions.

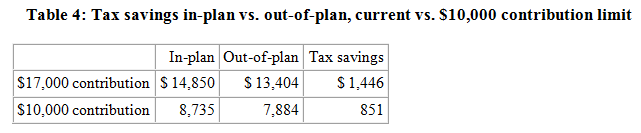

The following table compares the tax benefit (currently available) with respect to a maximum $17,000 contribution vs. the tax benefit if the 401(k) contribution limit were reduced to $10,000; we assume no change in the current 35% highest marginal tax rate.

The math here is pretty simple — a $7,000 reduction in savings, at 10 years, reduces the tax savings by $595, or 41%.

Changes in rates and contribution levels

Republicans have pushed for a comprehensive tax reform program that involves both a reduction in rates and the reduction/elimination of tax expenditures.

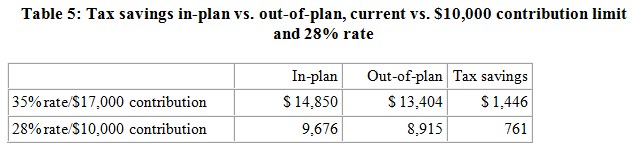

The following table considers the value of current tax treatment – 35% highest marginal rate and $17,000 401(k) contribution limit — with a 28% highest marginal rate and a $10,000 contribution limit.

The combination of a reduction in rates and a reduction in 401(k) contribution limits (to $10,000) reduces the tax savings by around $685, or 47%.

(We note that there have been various proposals to cap or otherwise limit deductions. The President (in his FY2013 budget) proposed capping certain tax preferences, including the 401(k) exclusion, at 28% for families earning over $250,000. Some policymakers have proposed capping “deductions” (presumably including the 401(k) exclusion) at $50,000. We have not modeled the consequences of these proposals, which in some cases are complicated and dependent on the taxpayer’s individual situation. If it appears that such an approach is a likely solution to the fiscal cliff, we will review it in detail.)

Capital gains and dividends

The lower tax rates for capital gains and dividends under the current Tax Code have also been a target for some who would like to raise revenues. Because a tax qualified plan trust is tax exempt, taxpayers who save through tax qualified plans generally don’t get the benefit of lower capital gains and dividends rates, and distributions from tax qualified plans are generally taxed at the higher ordinary income tax rate.

This tax treatment of capital gains and dividends generally reduces the tax benefit of saving in a qualified plan, relative to an investment that generates capital gains or dividends. If the tax rate on capital gains and dividends is increased, then the relative tax benefit of saving in a qualified plan will increase.

Conclusion

There’s a lot at stake in Congress’s deliberations with respect to the fiscal cliff. President Obama’s re-election, Democratic retention of control of the Senate, and Republican retention of control of the House may make it more likely that something will be done about the fiscal cliff in the lame duck session. How Congress addresses the issue of this issue could have a significant impact on retirement savings tax incentives. And it could easily go either way. Saving in a 401(k) plan could, from a tax perspective, become more attractive or less attractive.

We will continue to update you on this issue.