How efficient is the 401(k) system?

Closely linked to the criticism that the 401(k) system is unfair is a criticism that it is inefficient: that it does not do as good a job accumulating retirement savings as could be done.

While the “inefficiency” argument is complicated and involves a variety of issues, the elements of the system that have gotten the most attention are the issues of costs and fees. To oversimplify: there is concern that the nature of 401(k) plans creates costs and the potential for higher fees; as a result, the ultimate value of retirement savings is lower than it would be under a more efficient system.

In this article we review two recent papers highlighting these “efficiency critiques” – one from the General Accounting Office (GAO, who reports to Congress) and the other from Dēmos (an independent advocacy group).

As in our other articles in this series (e.g. Retirement savings tax incentives and the data), our purpose is not to advocate one view or another but to describe the terms of any forthcoming debate over changes to the 401(k) system in the context of comprehensive tax reform.

GAO report

The following is a summary of some of GAO’s key findings in its report 401(K) Plans: Increased Educational Outreach and Broader Oversight May Help Reduce Plan Fees.

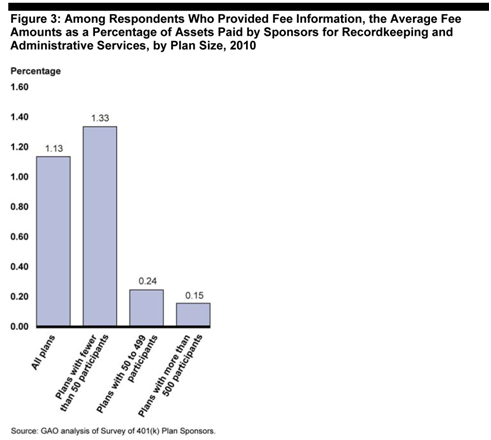

Small plans pay higher fees than large plans

It’s fair to say that most observers would agree with this conclusion. The degree to which small plan fees are higher than large plan fees, however, may be disputed. The chart below summarizes GAO’s findings:

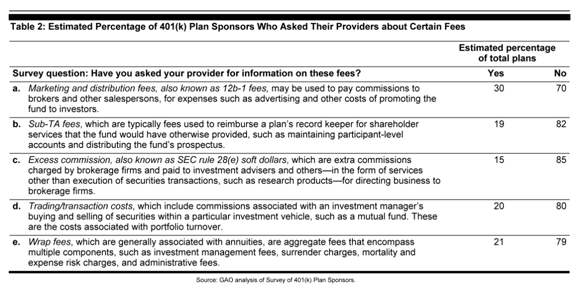

Many sponsors don’t ask, and are uninformed, about fees the plan pays

Certainly most would agree that some sponsors could do more to inform themselves about plan fees; the Tussey v. ABB case raises this issue. The extent to which GAO found that sponsors were uninformed and do not ask about fees, however, may be controversial. The following table illustrates GAO’s findings in this regard.

Plan sponsors are challenged by complex fee arrangements, and plans are likely to pay more than sponsors realize

It’s worth emphasizing this finding. A consistent theme of those criticizing the 401(k) system is that fee structures, and particularly revenue sharing-based fee structures, are complicated and make understanding and evaluating fees by sponsors more difficult than they should be.

A majority of sponsors do not know about commonly charged transaction costs

The issue of “transaction costs” is also highlighted in the Dēmos paper (discussed below). According to the GAO report:

SEC has identified four major types of mutual fund transaction costs: commissions, spread costs, market impact costs, and opportunity costs. However, no industrywide standard currently exists for calculating transaction costs. Different researchers and private sector companies have developed various methods to determine transaction costs. … Adding to the difficulty of estimating transaction costs is the fact that even though mutual funds have transaction costs associated with them, they are not uniformly measured or disclosed.

As we will discuss further below, the extent to which “only fees matter” — as opposed to “only net return matters” — is not dealt with in depth either in the GAO report, in the Dēmos paper or in the “efficiency critiques” of the 401(k) system generally.

DOL has improved Form 5500 data, but sponsors do not use the information

In what is likely to be a surprise to most sponsors, GAO believes that sponsors should, among other things, be mining Form 5500 data for comparative information about fees.

Recommendations

GAO recommends:

Better education. In order to help plan sponsors better understand how fees are charged to their plans and to help them make well-informed decisions, [GAO] recommend[s] that the Secretary of Labor develop and implement alternative approaches to Labor’s plan sponsor outreach and education initiatives that actively engage sponsors and allow the agency to track sponsor engagement.

Easier access to Form 5500 information. To help sponsors better understand and monitor plan fees, including those paid by participants, Labor should enhance web access to publicly available fee information it collects on the annual Form 5500 to provide sponsors with information to compare and assess fees charged by service providers, such as building in the ability to search for and create customized reports of plans with similar features or providers for the purpose of benchmarking. It should also consider developing and posting key information, such as a data dictionary, about the publicly available Form 5500 datasets on its website, similar to the information distributed about the Form 5500 research files.

Expanded definition of fiduciary. To help strengthen Labor’s ability to oversee 401(k) plans, [GAO] recommend[s] that in addition to Labor’s ongoing efforts, Labor should evaluate whether individuals and service providers who exert significant control over the plan should be considered ERISA fiduciaries.

The last recommendation is worth noting — it appears to be a call for an expansive definition of ERISA fiduciary. Generally, DOL’s (withdrawn) proposal to re-define who is an ERISA fiduciary was considered too expansive.

Methodology

We are not statisticians and are not qualified to evaluate GAO’s survey methodology. But we do observe the following: GAO’s conclusions are based on survey “data” — that is, on what, for instance, sponsors say their plans pay in fees. As it states in its report, through a variety of means that are themselves somewhat problematic, GAO determined that, e.g., some of the fee data reported by sponsors were in fact significantly incorrect.

Moreover, the survey sample, for small plans especially, looks small. For the two smallest groups, plans with fewer than 10 and 10-49 participants, from a total population of 354,921 plans, GAO sent surveys to 467 and got “in-scope” responses from 97 of those plans. So (whatever the statistical validity of the methodology), all of GAO’s conclusions with respect to these plans is based on data from 0.03% of the total population.

Dēmos paper

In a paper that has gotten considerable press attention, The Retirement Savings Drain; The Hidden & Excessive Costs Of 401(K)s, Dēmos found that 401(k) fees “are excessive—i.e. more than necessary to deliver excellent returns to savers — and can cost savers tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of their lifetimes.” The scare headline from Dēmos’s paper is — “Could Your 401(k) Fees Buy a House?”

Dēmos describes itself as “a non-partisan public policy research and advocacy organization … [working] with policymakers around the country in pursuit of four overarching goals — a more equitable economy with widely shared prosperity and opportunity; a vibrant and inclusive democracy with high levels of voting and civic engagement; an empowered public sector that works for the common good; and responsible U.S. engagement in an interdependent world.”

Dēmos identifies four types of fees paid by 401(k) plans: administrative fees; asset management fees; marketing fees (aka 12b-1 fees); and trading fees.

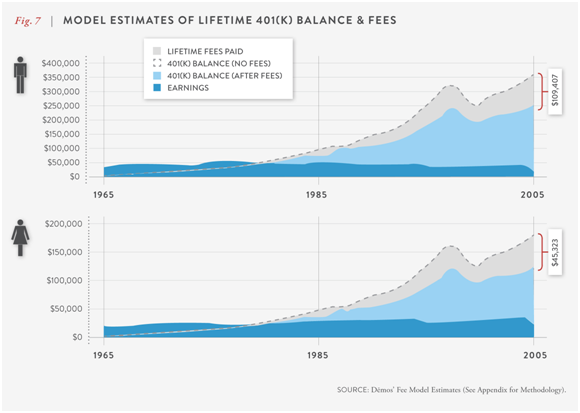

The following chart summarizes the fees (relative to savings) paid by an “ideal” retirement saver-couple.

The methodology here is a little complicated. Here’s Dēmos’s explanation:

To calculate how much [the four types of 401(k)] fees cost over a lifetime, we used a hypothetical two-earner household, each of whom earned the median income every year from age 25 to their retirement at 65, beginning in 1965 with steady contributions through 2005. We … assume that this household begins their career saving 5 percent of their combined gross income in a 401(k), and steadily increases 8 percent by retirement. We presume that they invest their savings equally in a mutual fund which invests primarily in bonds and a fund which focuses on stocks. The household’s stock and bond mutual funds each annually earn the average, index return for their asset class, and the returns on the household’s savings are compounded annually. As per the Investment Company Institute’s most recent data on fees, we assume these funds carry the (asset-weighted) mean expense ratio for their asset class: 0.72 percent for bond mutual funds and 0.95 percent for stock mutual funds. Finally, we presume, according to the consensus among retirement experts, including the CRR and Brightscope, that funds all have trading fees that equal the explicit expense ratio.

Based on this analysis, Dēmos finds that this couple, over a lifetime of savings, pays $154,730 in fees to produce a final account balance of $357,872.

Critique of Dēmos’s treatment of trading fees

Most of Dēmos’s methodology is in line with, e.g., the GAO’s approach and findings. One element, however, is very controversial — the estimation of “trading fees.”

Dēmos’s “trading fees” are at least part of what GAO calls “transaction costs:” “The costs incurred by the fund when buying and selling the securities (bonds, stocks, etc.) that comprise a mutual fund’s underlying assets.” Dēmos claims that it is “the consensus among retirement experts, including the [Center for Retirement Research] and Brightscope, that funds all have trading fees that equal the explicit expense ratio.” That is a big number — for a fund with a 1.25 percent expense ratio, Dēmos assumes an additional 1.25 percent in trading fees.

BrightScope has publicly disputed Dēmos’s trading fee assumption, saying that “Dēmos has probably overstated the average expense borne by individual participants by as much as 150 basis points.” (“Second Look at Headline Grabbing 401k Fee Survey Reveals Major Questions,” FiduciaryNews.com, June 5, 2012)

Fees vs. returns

A consistent push-back from supporters of the 401(k) system, against the fee-critics, has been that the focus on fees is misplaced, that what really matters is net returns. While the data on returns and, for instance, the value added by active management, is itself a matter of dispute, critics of the 401(k) system have generally stuck to the theme: “fees are too high” rather than engage on the issue of returns.

Other efficiency issues

Fees are, as it were, the sharp end of the stick in a broader critique of 401(k) plans. Other efficiency issues (“efficiency” here more or less standing for “how good 401(k) plans are at delivering retirement benefits”) include: inadequate coverage; requiring individual participants to bear longevity risk; asset/return volatility; and (poor) participant driven investment decisions.

DC assets are generally thought to underperform DB assets. According to Dēmos, the “National Institute on Retirement Security estimates that administering the average defined benefit plan, or traditional pension, costs 46 percent less than a typical 401(k) to provide the same benefit level in retirement, largely because of the higher fees and lower investment returns of 401(k)s and the ability of defined benefit plans to pool risk.”

Revolution or reform

According to Dēmos, the problems it identifies in the 401(k) system “cannot be solved by regulatory tweaks or even the increased transparency that the Department of Labor’s new [fee disclosure] rules will engender.” Dēmos explicitly advocates scrapping the 401(k) system and going to a system like that proposed by Dēmos Distinguished Senior Fellow Dr. Teresa Ghilarducci’s — the “Guaranteed Retirement Account.”

GRAs would be administered by the Social Security Administration, and “managed by the [Federal] Thrift Savings Plan or similar body. … The pooled funds [would be] conservatively invested in financial markets. However, participants [would] earn a fixed 3% rate of return adjusted for inflation, guaranteed by the federal government. If the trustees determine[d] that actual investment returns have been consistently higher than 3% over a number of years, the surplus [would] be distributed to participants, though a balancing fund [would] be maintained to ride out periods of low returns.”

Compared to Dēmos’s proposal, GAO’s proposals — the most “radical” being an expansion of the ERISA definition of fiduciary — are much more modest and envision the continuation and improvement of the current system.

We note that Dēmos is associated with critics of the fairness of the current system (including Professor Ghilarducci) (see our article Tax reform and 401(k) fairness). The Congressmen who requested GAO’s fee study — George Miller (D-CA and Ranking Member Committee on Education and the Workforce) and Robert E. Andrews (D-NJ and Ranking Member Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions, Committee on Education and the Workforce) — have also raised fairness issues. Together with J. Mark Iwry (Senior Advisor to the Secretary of the Treasury and the Deputy Assistant Secretary (Tax Policy) for Retirement and Health Policy at the U.S. Treasury Department) and William G. Gale of the Brookings institution, these groups and individuals represent the spectrum of criticism of the 401(k) system, from those who want to overturn it to those who simply want to make it better.

Consequences for policy

We have gone over the “findings” and claims of GAO and Dēmos in detail not simply to repeat their criticisms but to provide an idea of the sorts of issues that one constituency — those who view the 401(k) system critically — will bring to the table in any comprehensive reconsideration of 401(k) tax provisions.