PBGC premium increases and the FY2013 annual report

On December 10th, Congressional budget negotiators agreed on a short-term deal intended to forestall federal budget crises for the coming year. As part of the deal, PBGC premiums will increase substantially compared to current law beginning in 2015. A summary of the provisions of the agreement can be found here.

Recently, the PBGC released its FY2013 annual report (PBGC runs on an October 1-September 30 fiscal year), which includes news on PBGC’s financial condition and arguments in favor of higher PBGC premiums. In this article, we review PBGC’s finances and consider the case for higher premiums.

Headlines

Here are the headlines from PBGC’s FY2013 annual report:

PBGC’s deficit continues to worsen. “PBGC’s combined financial position declined by $1,260 million, increasing the deficit to $35,639 million as of September 30, 2013, from $34,379 million as of September 30, 2012.”

The primary reason for this weak financial position is that premiums established by Congress are inadequate to cover insured benefits.

Without the tools to set its financial house in order, PBGC may face for the first time the need for taxpayer funds. Indeed, “barring changes, neither [the single-employer nor the multiemployer] program will be able to fully satisfy PBGC’s obligations to plan participants in future years.”

As discussed below, the facts do not seem to justify these assertions.

What the numbers actually say

PBGC maintains two separate and financially unrelated insurance programs. Our focus is the single-employer program. The financial position of the single-employer program did not worsen over FY2013, it improved: “the single-employer program’s net position increased by $1,761 million, decreasing the program’s deficit to $27,381 million.” The multi-employer program, which is in serious trouble, did get much worse.

Consider the assets and liabilities of both programs.

Single-employer | Multiemployer | |||

2013 | 2012 | 2013 | 2012 | |

Assets | $83,227 | $82,973 | $1,719 | $1,807 |

Liabilities | $110,608 | $112,115 | $9,977 | $7,044 |

Net | ($27,381) | ($29,142) | ($8,258) | ($5,237) |

Assets/Liabilities | 75% | 74% | 17% | 26% |

In the single-employer program, assets went up and liabilities went down in 2012-2013. In the multiemployer program the reverse happened. In the single-employer program, assets are 75% of liabilities; in the multiemployer program assets are only 17% of liabilities.

Calculating liabilities

The method by which PBGC calculates its liabilities is, at best, not very transparent. Critically, PBGC’s interest rate numbers seem to lag the performance of other indexes and do not reflect significant increases in interest rates over the period September 2012-September 2013.

Here’s PBGC’s description of how it calculates valuation interest rates for 2013:

For FY 2013, PBGC used a 20 year select interest factor of 3.25% followed by an ultimate factor of 3.32% for as long as benefits are to be paid. In FY 2012, PBGC used a 25-year select interest factor of 3.28% followed by an ultimate factor of 2.97% for the remaining years. These factors were determined to be those needed (given the mortality assumptions), to continue to match the survey of annuity prices provided by the American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI). Both the interest factor and the length of the select period may vary to produce the best fit with these prices. The prices reflect rates at which, in PBGC’s opinion, the liabilities (net of administrative expenses) could be settled in the market at September 30, for the respective year, for single-premium nonparticipating group annuities issued by private insurers. Many factors may affect these rates, including Federal Reserve policy, changing expectations about longevity risk, and competitive market conditions.

PBGC’s select rate (liabilities of 20 years or less) can reasonably be compared to the Pension Protection Act (PPA) second segment rate; its ultimate rate (liabilities over 20 years) can be compared to the PPA third segment rate. The PBGC rates will of course be lower, because annuity purchase rates are generally lower than the corporate bond yield curve used for PPA valuations. But the direction and amount of change of the rates should be similar. From September 2012 to September 2013, the PBGC select rate went down 3 basis points; the PPA second segment rate went up 95 basis points. From September 2012 to September 2013, the PBGC ultimate rate went up 31 basis points; the PPA third segment rate went up 95 basis points.

The general trend for long-term interest rates since September 30, 2012 has been up. We would expect that trend ultimately to be reflected in PBGC’s valuation of its liabilities, reducing the (according to the current annual report) $110 billion in liabilities by $5 to $10 billion. Unless there is something more mysterious (and even less transparent) going on.

Underwriting performance

Earlier this year, we posted an article on PBGC’s deficit that, among other things, reviewed PBGC’s underwriting performance – premiums vs. the gains (losses) from terminations – back to 2002. We went back to 2002 because at the beginning of 2002 PBGC was in surplus. The point of this comparison was to determine whether PBGC’s decline into deficit was attributable to underwriting losses – that is, because premiums were too low. Below is the table from that earlier article, updated through 2013.

Losses from Completed and Probable Terminations, Plus Expenses, Less Net Premium Income ($ billions)

Year | Loss From Completed and Probable Terminations | Expenses | Net Premium Income | Net Increase in Deficit |

2002 | 9.31 | 0.22 | (0.79) | 8.74 |

2003 | 5.38 | 0.39 | (0.95) | 4.82 |

2004 | 14.71 | 0.25 | (1.46) | 13.50 |

2005 | 3.95 | 0.42 | (1.45) | 2.92 |

2006 | (6.16) | 0.41 | (1.44) | (7.19) |

2007 | 0.40 | 0.49 | (1.48) | (0.59) |

2008 | (0.83) | 0.41 | (1.34) | (1.76) |

2009 | 4.23 | 0.43 | (1.82) | 2.84 |

2010 | 0.51 | 0.44 | (2.23) | (1.28) |

2011 | 0.20 | 0.45 | (2.07) | (1.43) |

2012 | 2.01 | 0.44 | (2.64) | (0.19) |

2013 | 0.47 | 0.44 | (2.94) | (2.03) |

12-Year Total | 34.18 | 4.79 | (20.61) | 18.35 |

So, PBGC does have an underwriting ‘deficit’ – the value of terminations has exceeded premiums over the period 2002-2013 by $18.35 billion. But this deficit, and more, is entirely attributable to the period 2002-2006, when total underwriting losses amounted to $22.79 billion, due in part to multiple airline bankruptcies. In the past seven years, by contrast, the PBGC has enjoyed underwriting profits of $4.44 billion.

Higher premiums are a big part of the story. In 2005 the flat-rate premium was increased from $19 per capita to $30; in 2012, under the “Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act” (MAP-21), the flat-rate premium will go up to $49 in 2014, and the variable-rate premium will generally double by 2015.

Asset performance

PBGC single-employer program assets earned 2.6% for the period September 2012-September 2013. PBGC uses generally (more on this below) a 30/70 equity/fixed incme asset allocation. The 2.6% result outperformed PBGC’s own benchmark (which was at 2.1%), but it significantly underperformed the statutory alternative (‘ERISA’) benchmark, which uses a 60/40 asset allocation and returned 10.7% for the same period.

PBGC’s asset allocation strategy

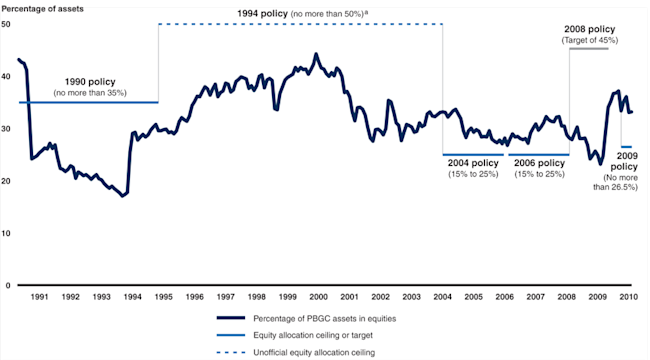

Many consider PBGC’s asset allocation strategy problematic. Here’s what the Government Accountability Office said about it in its 2011 report:

Since 1990, PBGC has shifted its investment policy five times. The shifts in investment policy that occurred in 1990 and 2004 were aimed at strategies that immunized against interest rate exposure by increasing the allocation of fixed-income securities. PBGC’s investment policy was shifted in 2009 to a more conservative strategy of taking on a higher allocation of fixed-income securities. In contrast, shifts in investment policy that occurred in 1994 and 2008 were aimed at strategies that maximized returns by increasing the allocation of equities. Shifts in policy of this frequency are thought to reflect an undisciplined approach to investing. Experts we interviewed stated that a more disciplined approach would require that PBGC change its investment policy no more than once every 5 to 7 years, except to review the policy during unusual circumstances, such as the recent market crash or when taking over the assets of a large terminated plan. They noted that it can take up to 5 years for a policy to be fully implemented and to have an impact that can be evaluated. Moreover, these experts stated that a long-term and disciplined investment policy is needed in order to minimize the costs associated with shifts in policy. Since 1990, PBGC’s investment policy was in place for more than 5 years only once—during the period from 1994 to 2004. All other policies were in place for shorter periods, generally about 2 to 4 years (see fig. 3).

There has also been a problem with conformance to these changing investment policies. In its report GAO provided the following chart, comparing PBGC’s actual asset allocation to its asset allocation policy.

Risk to the system

In the FY 2013 annual report PBGC asserts: “Absent changes, eventually we will have insufficient funds to pay benefits.” This assertion is contradicted by PBGC’s own simulation models. Quoting from last year’s GAO report:

[O]ut of 5,000 [Pension Insurance Modeling System] simulations, none project that PBGC’s single-employer program will run out of money within the next 10 years (fiscal year 2020). In the PIMS projection for the PBGC 2010 Annual Report, 2.5% of the simulations project that the program will run out of money by fiscal year 2030. A slight majority of the simulations result in improved or unchanged positions.

Note that this conclusion was reached before the enactment of MAP-21, which dramatically increased PBGC premium rates.

Improvement in single-employer plan funding

Perhaps the most significant improvement in PBGC’s risk position has nothing to do with its own finances at all. The funding position of private US defined benefit plans has improved significantly over the last year. The current funded ratio of private US DB plans is estimated to be about 95%, reflecting strong positive experience in 2013 – a year ago, the typical funded ratio was around 75%. The main point here is that this improvement in private company DB funding significantly reduces the risk to PBGC’s single-employer system. But it also raises the question – why hasn’t PBGC’s funding improved as well?

What is PBGC’s problem?

Like last year’s GAO report, PBGC’s FY2013 annual report is a work of advocacy. PBGC’s message is: PBGC’s financial position is worse, and unless it is given authority to set premiums for single-employer plans, taxpayers will ultimately have to bail it out:

Our financial position remains in deficit for both single-employer and multiemployer programs. The primary reason is that premiums established by Congress that we are permitted to charge are inadequate to cover the benefits that, by law, we insure. Our programs remain on the Government Accountability Office’s High Risk List with a net accumulated financial deficit of $36 billion in FY 2013. The Administration again proposed risk related premiums for PBGC in its 2014 budget. The proposal authorizes the PBGC Board to adjust premiums to better account for the risk the agency is insuring and make the premium structure fair to all premium payers. Absent changes, eventually we will have insufficient funds to pay benefits. … Without the tools to set its financial house in order, PBGC may face for the first time the need for taxpayer funds.

The numbers, however, tell a different story:

1. While the multiemployer program seems headed for insolvency, the financial position of PBGC’s single-employer program is improving. In that regard, recent increases in interest rates, which do not appear to be reflected PBGC’s 2013 numbers, are likely to significantly reduce the single-employer plan program deficit.

2. There does appear to have been an underwriting problem – inadequate premiums – for the period before 2006. But we have had three significant premium increases since then including the increases due to the December 2013 budget deal, while PBGC’s current premium rate appears to be more than enough to cover current terminations.

3. PBGC’s asset allocation strategy has been criticized by, among others, the GAO. Its asset performance in the current year appears adequate (for a 30/70 asset allocation), but it’s not unreasonable to attribute a meaningful piece of PBGC’s historical deficit to prior asset allocation decisions.

4. It’s not clear that PBGC’s ‘deficit’ is the best way to assess the risk to the single-employer insurance program. Certainly, the deficit of the multiemployer program (which PBGC confusingly combines with the single-employer program deficit) is irrelevant. But, in any case, the single-employer program deficit does not reflect the risk that is ‘out there’ with respect to plans that haven’t terminated. In that regard, you would think that the simulations PBGC has itself done would be more relevant, and those simulations seem to show that there is no problem.

* * *

PBGC remains committed to its proposal that it be given authority to increase premiums, particularly on what it deems to be financially ‘risky’ plan sponsors. Last year’s GAO report, the Administration’s budget and the FY2013 annual report all strongly advocate this position. It appears, however, that the reasons given for doing so are not supported by the facts.

As the PBGC said in its report, “Unfortunately, our premiums are set in law.” So far, PBGC’s proposal has faced opposition in Congress, particularly in the House. Thus, absent a change in control in Congress, PBGC’s proposal is not likely to become law any time soon.