The fiscal cliff and retirement plans: ‘caps on deductions’

The fiscal cliff and retirement plans: 'caps on deductions'

We have written several times about proposals to change the Tax Code and the effect of such proposals on, e.g., 401(k) plan participants. There is currently talk, in connection with ‘avoiding the fiscal cliff,’ of ‘capping’ retirement savings tax benefits, generally in connection with a broader cap on tax deductions or tax preferences or tax expenditures. In this article we consider, first, some of the conceptual problems that such a cap would present, and, second, how a cap might affect participants.

Background — caps generally

There is, generally, a lot of discussion (as of this writing, mainly from Republicans) about raising revenues by ‘capping deductions.’ Governor Romney suggested (possibly) capping deductions at $50,000. More recently (and post-election) there is talk of a $25,000 cap or, alternatively, a cap equal to 15% of income.

A different sort of proposal — in effect, a cap on (or reduction of the value of) tax preferences generally — was put forward in the Administration’s FY2013 budget (published in February, 2012). It called for a reduction in the value of itemized deductions and other tax preferences, including retirement savings tax incentives, to 28% for joint filers with income over $250,000.

These sorts of proposals address broad tax policy — reducing the total tax benefits taxpayers (generally, high income/high deduction taxpayers) can get. There has also been talk of specifically capping retirement savings tax incentives. For the most part these proposals have been vague, e.g., the Simpson-Bowles proposal to “cap tax-preferred contributions to the lower of $20,000 or 20% of income.”

Technical issues

With respect to retirement savings tax incentives, each of these approaches presents technical issues that may affect the end result.

First, what do you do about defined benefit plans? Contributions to defined contribution plans are allocated to individual accounts, but DB contributions aren’t. Applying an individual taxpayer ‘deduction cap’ to DB benefits (or contributions) would present daunting conceptual and technical challenges, and no one has suggested doing so. But capping only contributions to DC plans seems to be more a ‘tax on plan type’ than a reduction in retirement savings tax benefits.

The latter point is worth emphasizing. By what theory does it make sense to (in effect) tax DC benefits at a higher rate than DB benefits? There are some that think that DB plans are better and fairer, but there are others who think DC plans are better and fairer. Should Congress be picking sides in this fight?

Second, how would you implement a cap that included defined contribution plan tax benefits? The idea of ‘reducing tax preferences’ for DC plans seems relatively intuitive, but it does not fit automatically into, e.g., a rule that says: total deductions can’t exceed $25,000. Participants don’t take deductions for DC contributions. You could provide that allocations to a participant’s account count against the $25,000 limit on deductions — but what if the account doesn’t vest?

This approach — counting DC contributions as deductions — might work for 401(k) contributions. In effect, you could give the participant a choice between taking a deduction for mortgage interest or contributing to the 401(k) plan. But the mechanics are a lot more awkward for non-401(k) contributions.

Generally, if Congress wanted to ‘raise revenues’ by reducing the tax expenditure for retirement savings tax incentives, it would be much easier to simply reduce the limits on, e.g., DC contributions. But such an approach would not fit in with the idea of a simple ‘cap’ on total deductions.

Effect on participants

We have written recently about the effect of, e.g., a reduction in 401(k) plan contribution limits on the value of a 401(k) plan for high income participants. The impact of many of these proposals is relatively intuitive. For instance, if a participant is forced to choose between taking a ‘deduction’ for a 401(k) contribution or taking a deduction for her mortgage interest, she will probably take the deduction for the mortgage interest (that is money she has to pay) and not contribute to the plan.

In what follows, we want to illustrate one effect of some of the cap proposals under consideration that may not be intuitive. We’ll consider the President’s proposal to limit the value of the retirement savings tax preference to 28% for joint filers making over $250,000. The contribution will get a 28%‘deduction’ going in, but it will be fully taxable when distributed, at a 35% rate.

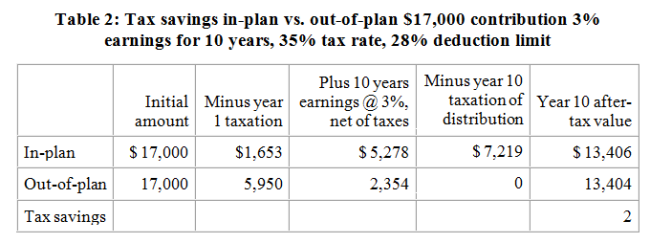

As in the prior analyses of tax effects we have done, we’ll assume the participant leaves the money in the plan for 10 years and that in the plan it earns 3% per year. What is the value of that $17,000 (the maximum 401(k) deferral for 2012) after 10 years, net of taxes vs. paying taxes immediately and saving the $17,000 outside the plan?

We begin with a baseline — the value of in-plan savings under current rules. Table 1 shows the tax saving (after 10 years) the participant realizes if she saves in the plan rather than outside of it. (For a full discussion of our methodology, see our article The ‘fiscal cliff’ and retirement plan participants.)

Bottom line, with these assumptions, under current tax rules, the participant has $1,446 more in 10 years than she would have had if she had saved outside the plan.

Now, what happens if the exclusion in year 1 is limited to 28%? We interpret this to mean that the participant will pay a tax in year 1 of 7% (assuming a 35% tax rate and 28% deduction) but will (assuming constant tax rates) pay a tax on distribution of 35%. Taking the analysis a step further, the $17,000 must fund both the contribution and the current taxes owed, and any amount ‘held back’ for taxes is itself taxed at the full 35% rate. The amount ‘held back’ to cover taxes, in our example, is $1,653 [$17,000 x (35% – 28%) / (1-28%)], leaving $15,347 available for ‘in-plan’ savings. Table 2 shows the tax savings under these assumptions:

The result is astonishing – the value of the tax benefit is essentially eliminated in our example, merely by limiting the ‘upfront’ tax deduction to 28%.

Implications

The President’s proposal (and any other proposal that would limit the value of the ‘deduction’/exclusion ‘going in’) would presumably apply to 401(k) contributions, but may also be extended to other DC plans. It could even conceivably be applied to DB plans, although it is hard to imagine how that would work. Such a change would likely have a dramatic effect on the appeal of affected plans to participants paying taxes above, e.g., the 28% rate.

* * *

We still don’t have a lot of specifics on these ‘cap’ proposals. And we have no idea whether one of them will be in a deal on the fiscal cliff or, e.g., a future deal on comprehensive tax reform. But of all the proposals being considered by policymakers, the ones involving a cap on tax deductions/preferences has the greatest potential for affecting retirement plans negatively. We will continue to update you on this issue.